Born Again

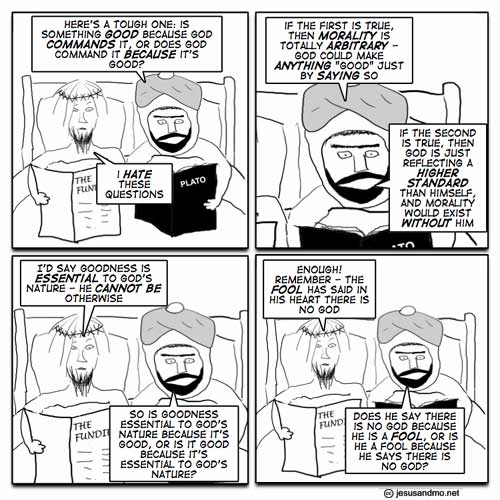

I like calling my exodus from Mormonism and religion an “awakening” because that’s what it felt like. Domokun reminded me of Plato’s cave allegory and how well it describes what leaving religion has felt like for me.

Imagine prisoners, who have been chained since their childhood deep inside a cave: not only are their limbs immobilized by the chains; their heads are chained in one direction as well, so that their gaze is fixed on a wall.

Behind the prisoners is an enormous fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway, along which statues of various animals, plants, and other things are carried by people. The statues cast shadows on the wall, and the prisoners watch these shadows. When one of the statue-carriers speaks, an echo against the wall causes the prisoners to believe that the words come from the shadows.

The prisoners engage in what appears to us to be a game: naming the shapes as they come by. This, however, is the only reality that they know, even though they are seeing merely shadows of images. They are thus conditioned to judge the quality of one another by their skill in quickly naming the shapes and dislike those who play poorly.

Suppose a prisoner is released from his cage and turns around. Behind him he would see the real objects that are casting the shadows. At that moment his eyes will be blinded by the sunlight coming into the cave from its entrance, and the shapes passing by will appear less real than their shadows.

The prisoner then makes an ascent from the cave to the world above. Here the blinding light of the sun he has never seen would confuse him, but as his eyesight adjusts he would be able to see more and more of the real world. Eventually he could look at the sun itself, that which provides illumination and is therefore what allows him to see all things. This moment is a form of enlightenment in many respects and is understood to be analogous to the time when the philosopher comes to know the Form of the Good, which illuminates all that can be known in Plato’s view of metaphysics.

Once enlightened, so to speak, the freed prisoner would not want to return to the cave to free “his fellow bondsmen,” but would be compelled to do so. Another problem lies in the other prisoners not wanting to be freed: descending back into the cave would require that the freed prisoner’s eyes adjust again, and for a time, he would be one of the ones identifying shapes on the wall. His eyes would be swamped by the darkness, and would take time to become acclimated. Therefore, he would not be able to identify the shapes on the wall as well as the other prisoners, making it seem as if his being taken to the surface completely ruined his eyesight.

Tags: Atheism, Awakening, belief, conversion, epistemology, idolatry, ignorance, illusion, LDS, liberty, mindfuck, Mormonism, philosophy, Plato, religion, superstition, truth